section⁄Still, we are not robots

This final section collects documents, fragments and insights that connect the past stories gathered in these pages with the present time. The last two decades have been marked by a new cycle of automation and other technological changes in the ways people work, heal, live and protest. Without pretense of being exaustive, we gathered materials that resonate with the four red threads introduced in the previous sections: techniques of exploitation; health and environmental conditions; gendered discrimination; and forms of resistance.

The story from which we start: Still, we are not robots¶

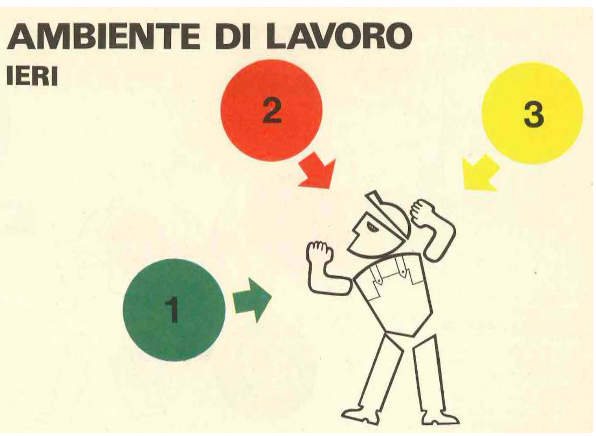

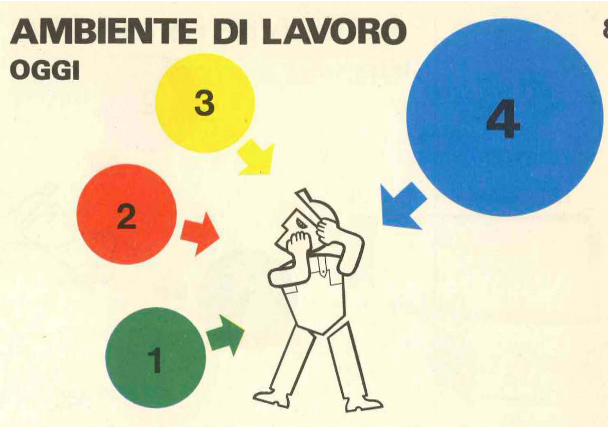

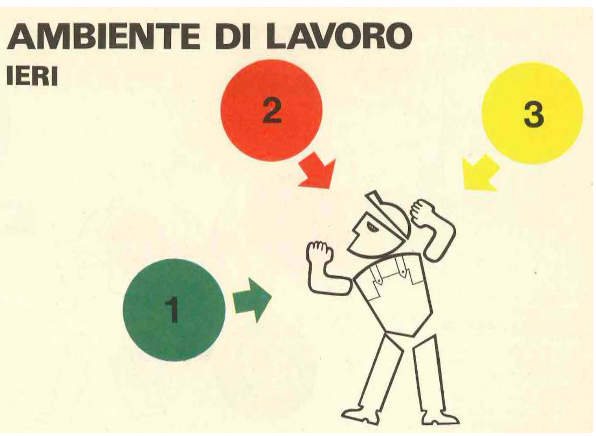

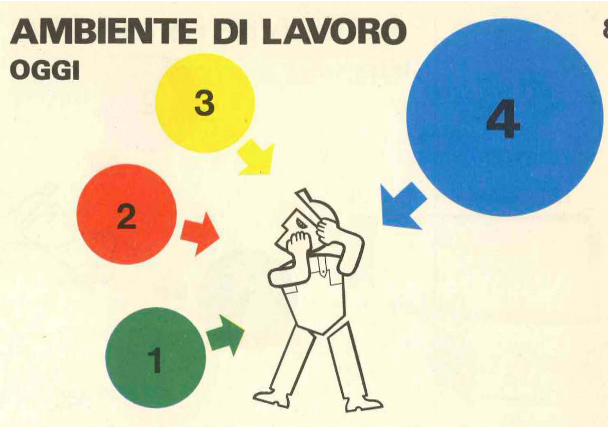

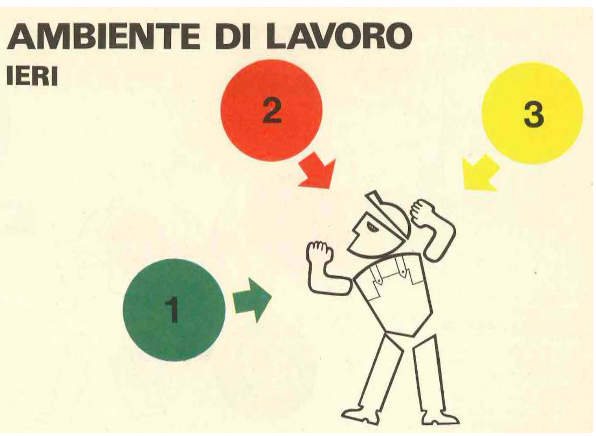

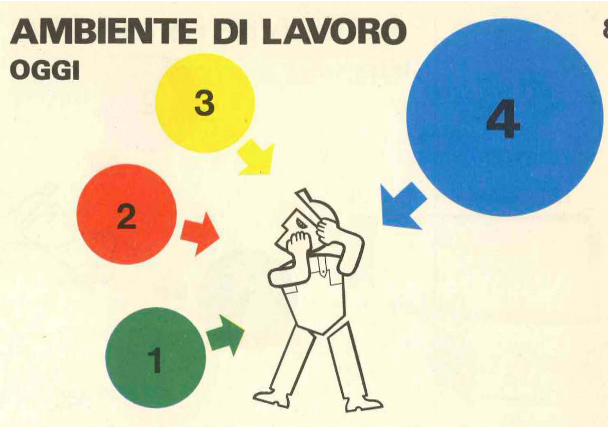

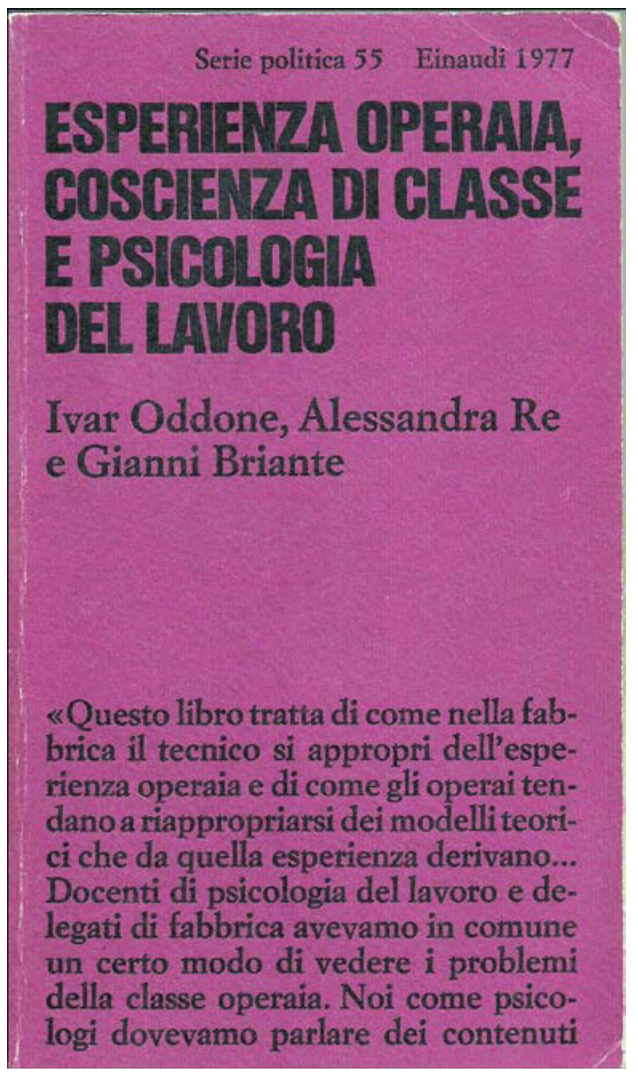

The Work Environment first produced at FIAT and Against Noxiousness of Porto Marghera agreed in identifying one mid-term tendency crucially relevant in our present times: mental noxiousness.

In the language of The Work Environment, this was the idea that while the first 3 factors of noxiousness were going to be mitigated by tendencies within capitalism itself, the 4th factor pertaining to mental wellbeing was going to get worse:

the work environment yesterday

the work environment today

While in Against Noxiousness we can read:

In the new factory, coupled with a modest reduction in toxicities and thus in occupational diseases traditionally understood, there will be a strong increase in mental health disorders

“Against Noxiousness” (Comitato Politico, 28 February 1971).

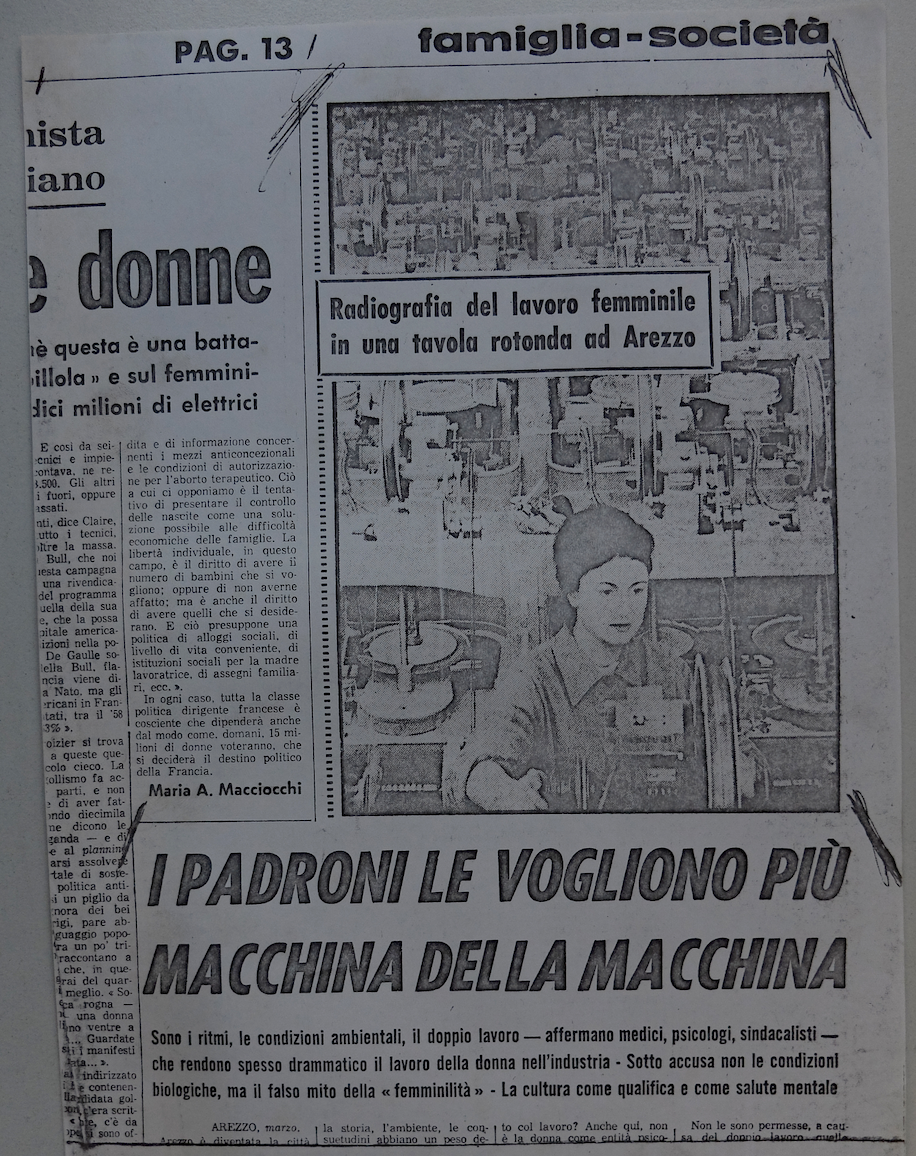

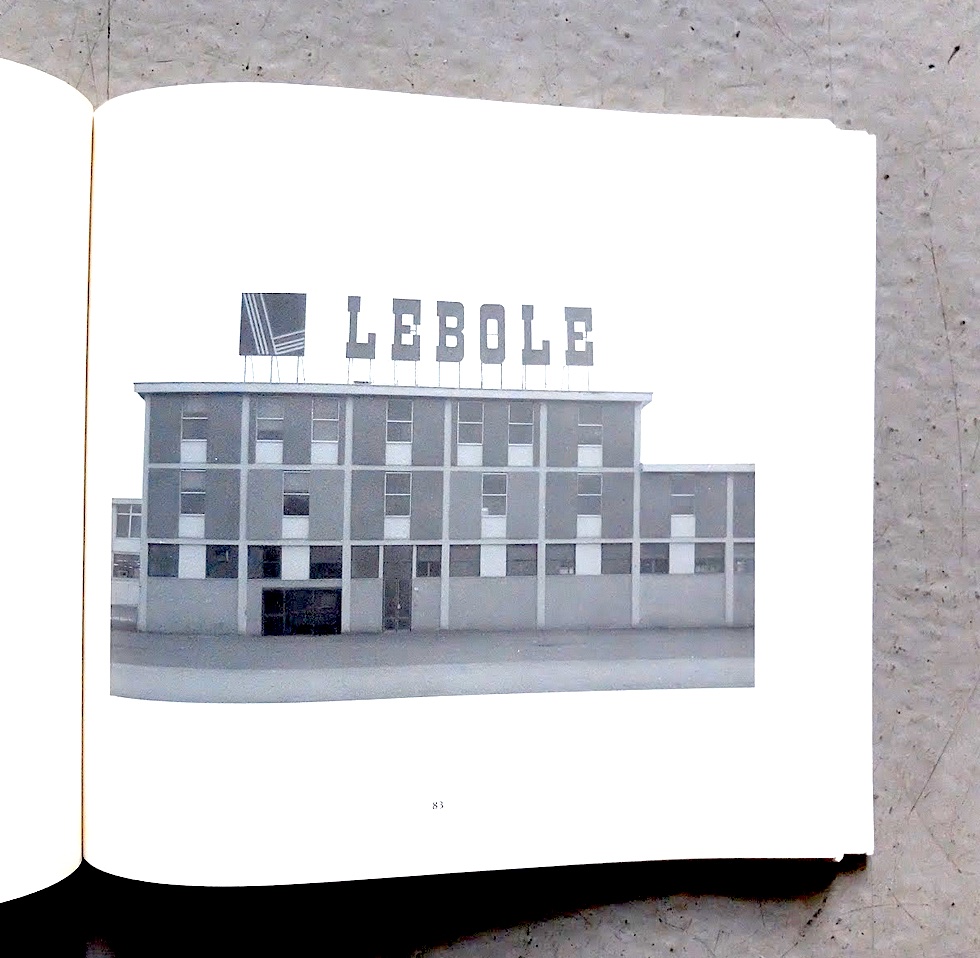

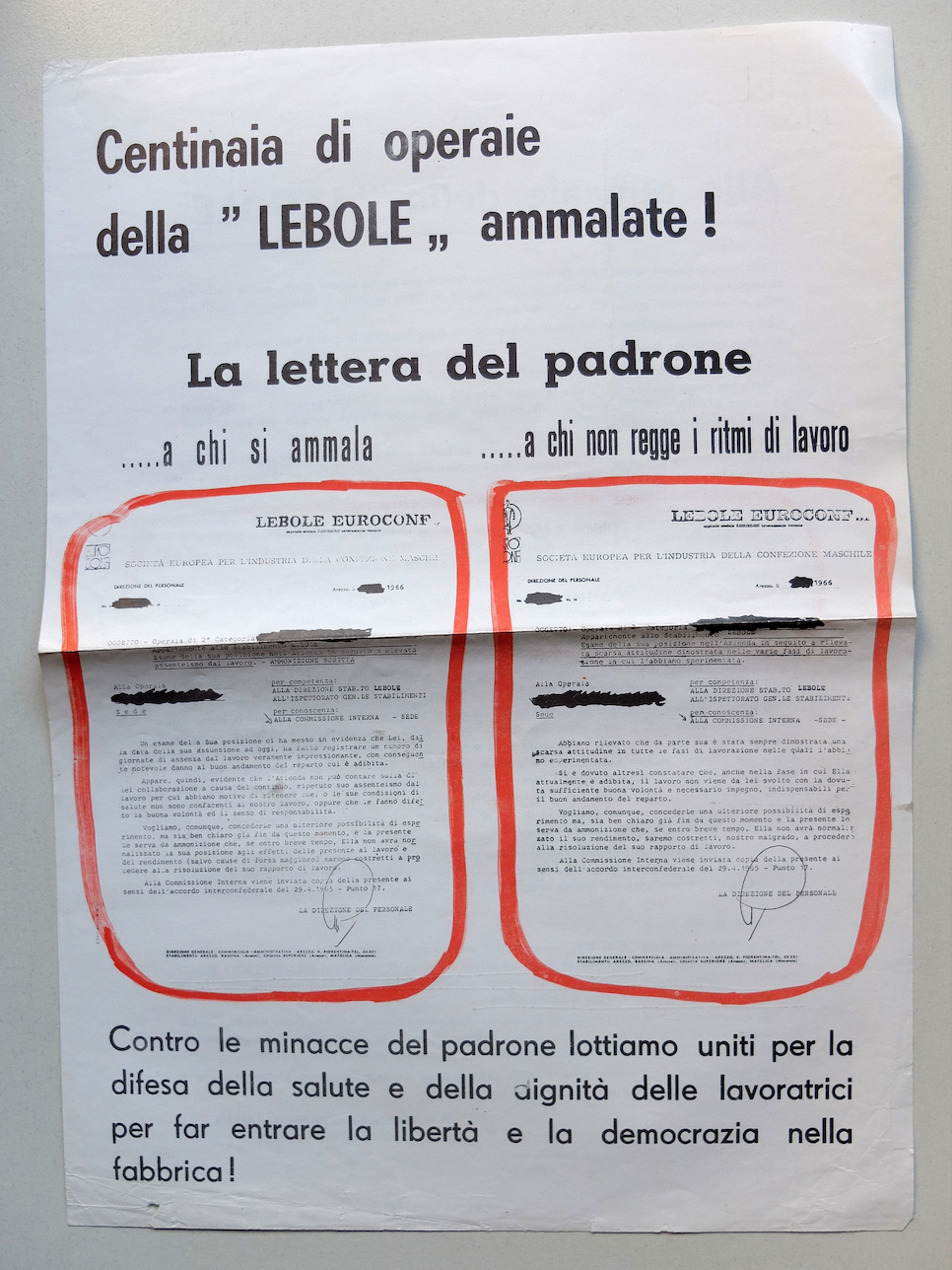

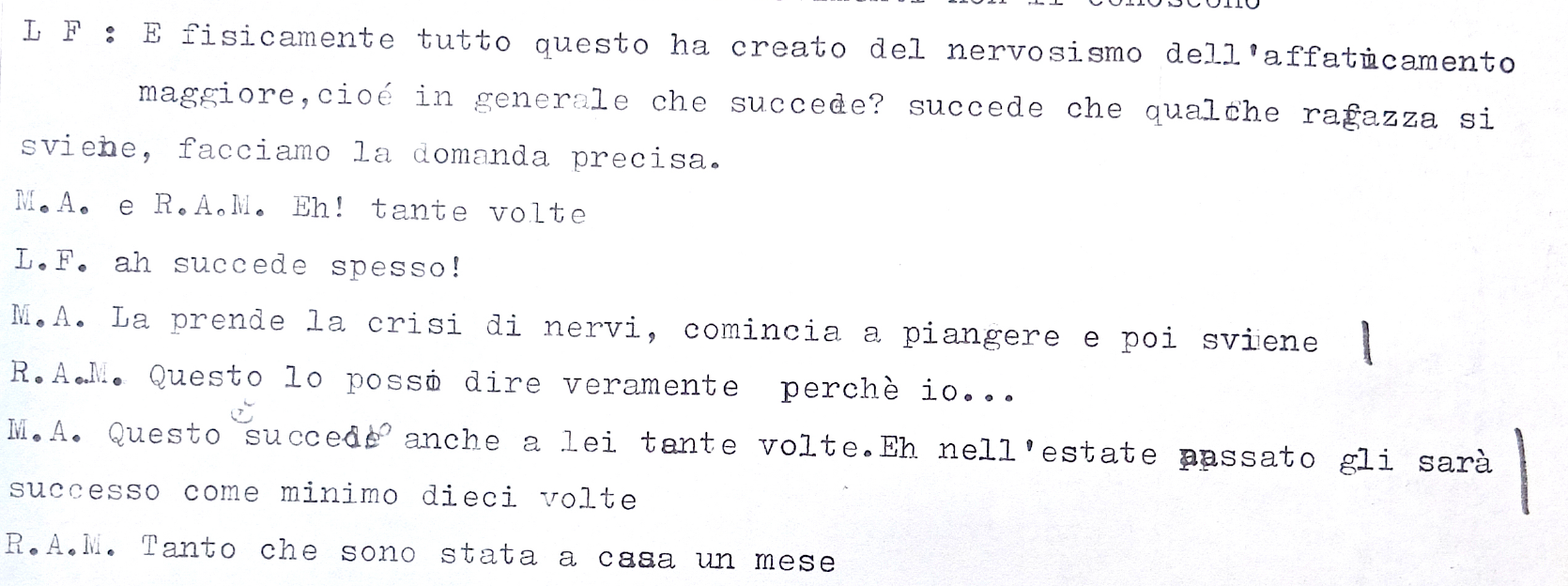

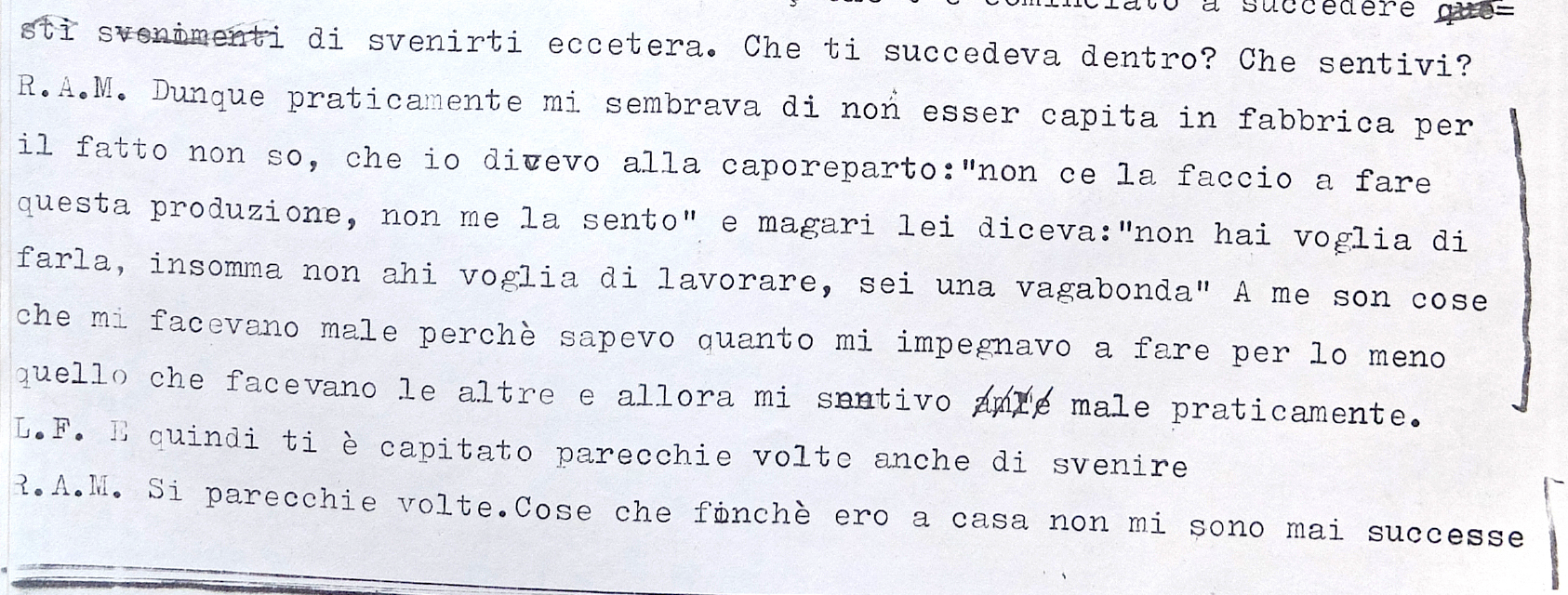

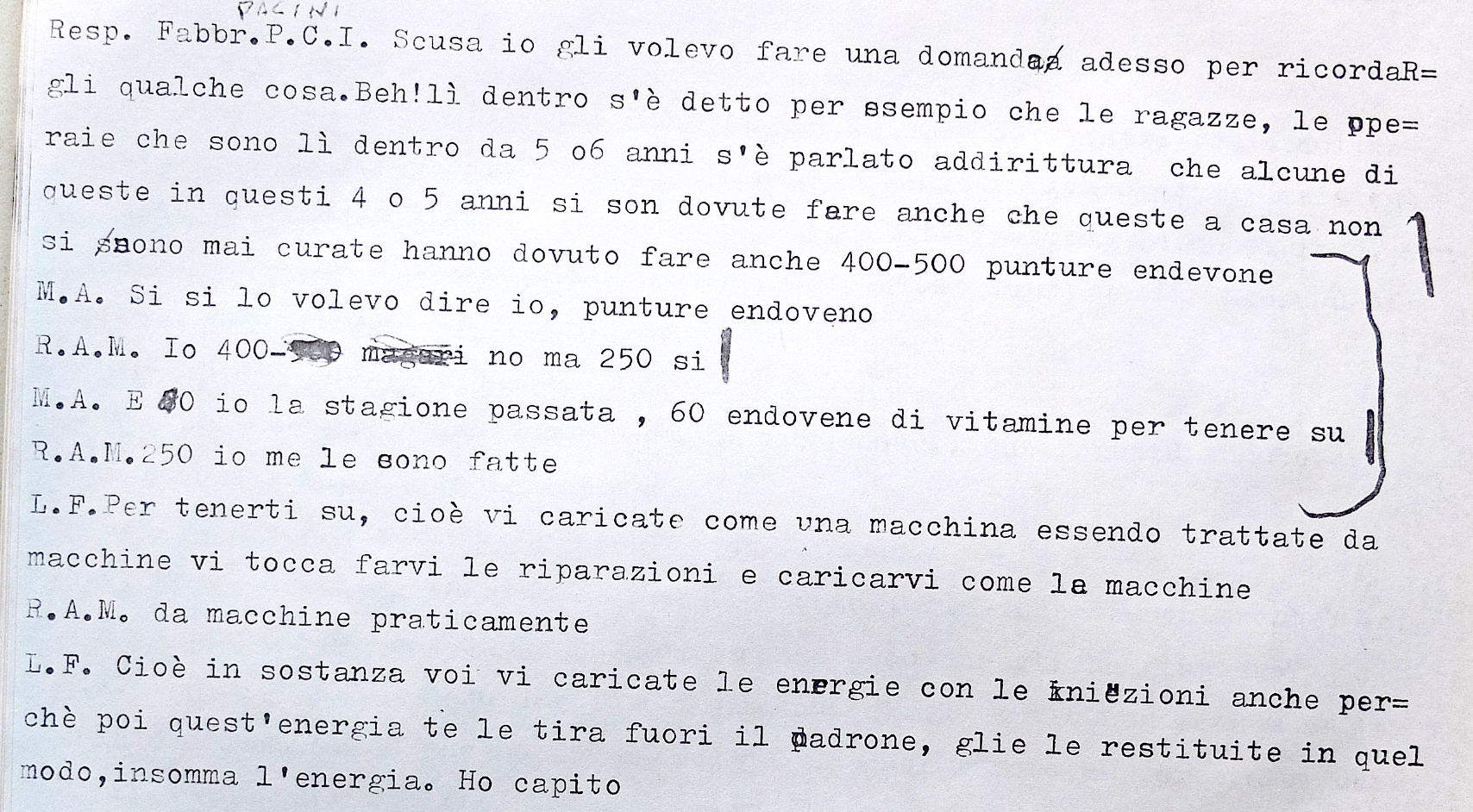

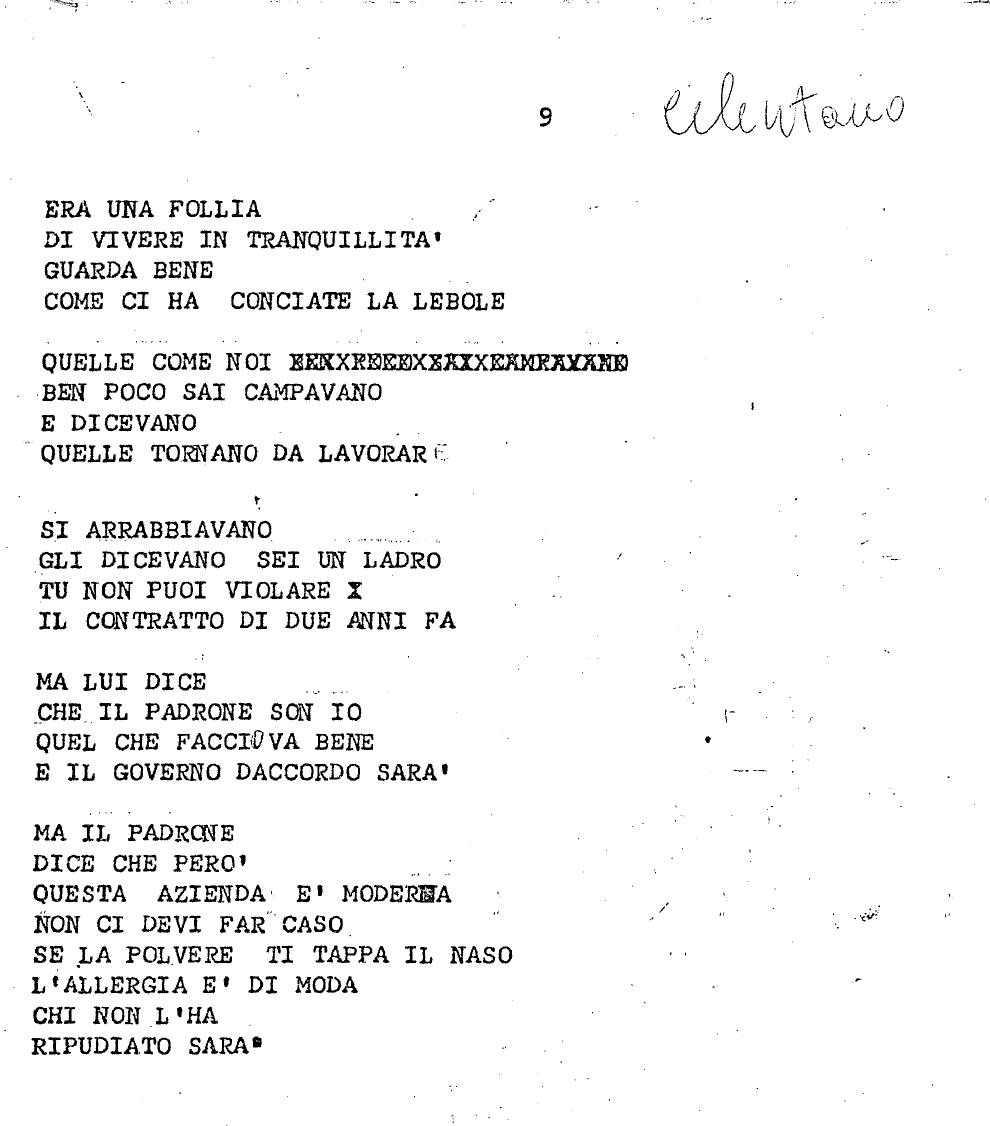

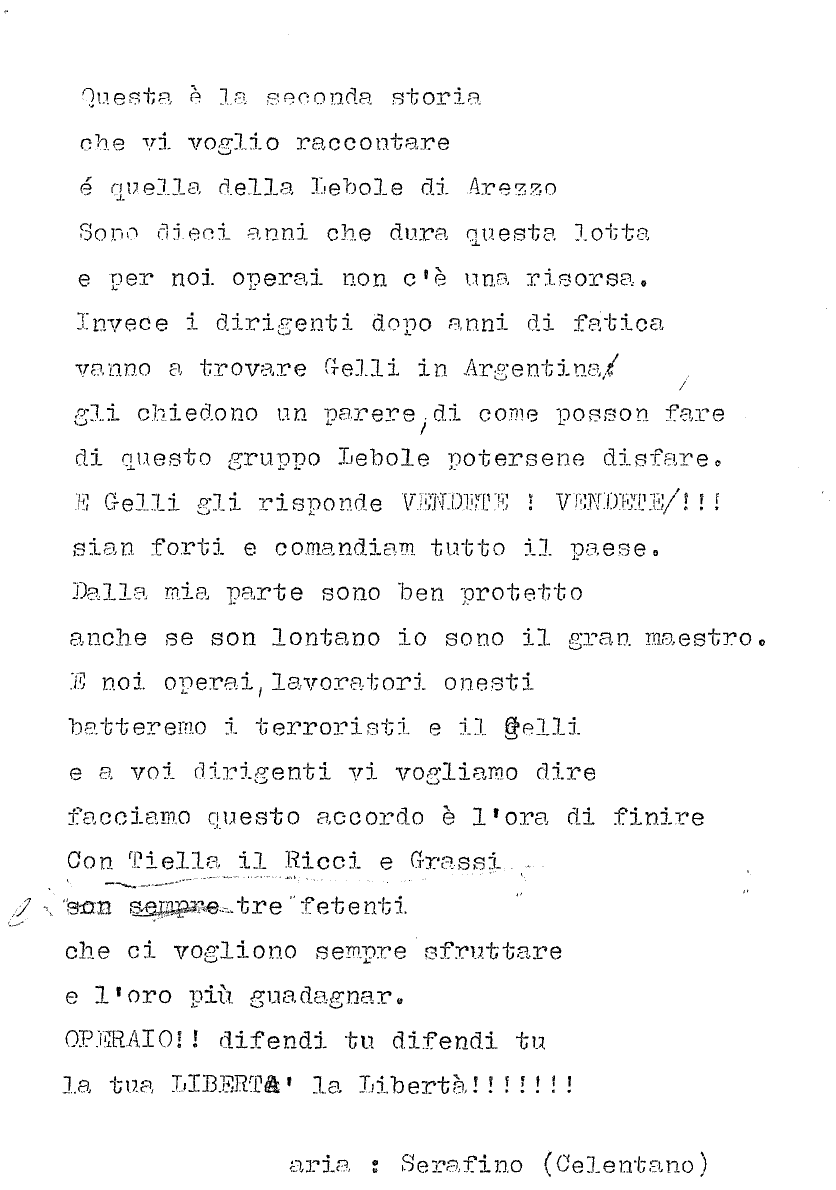

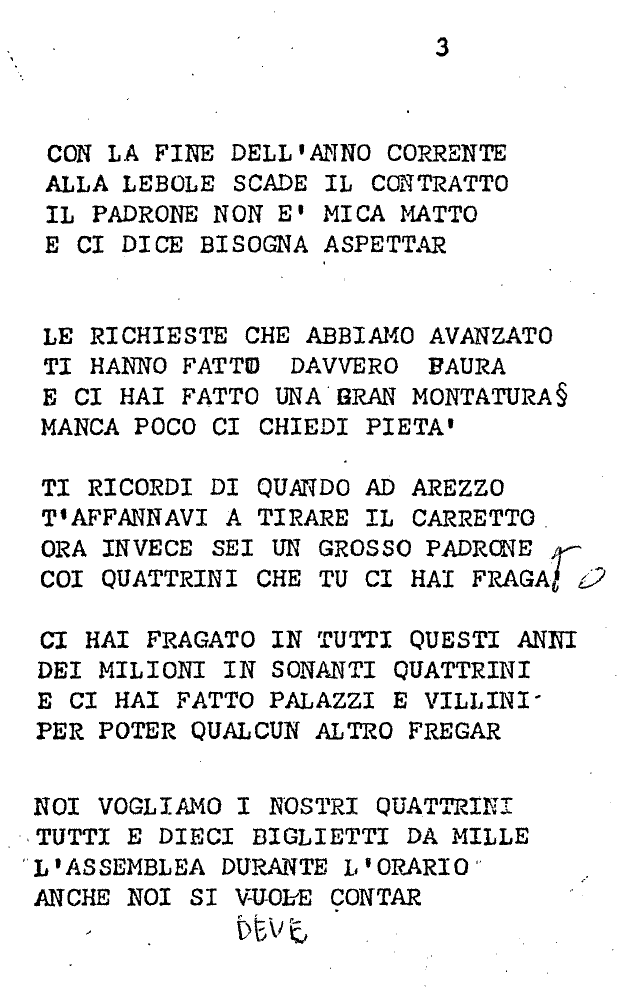

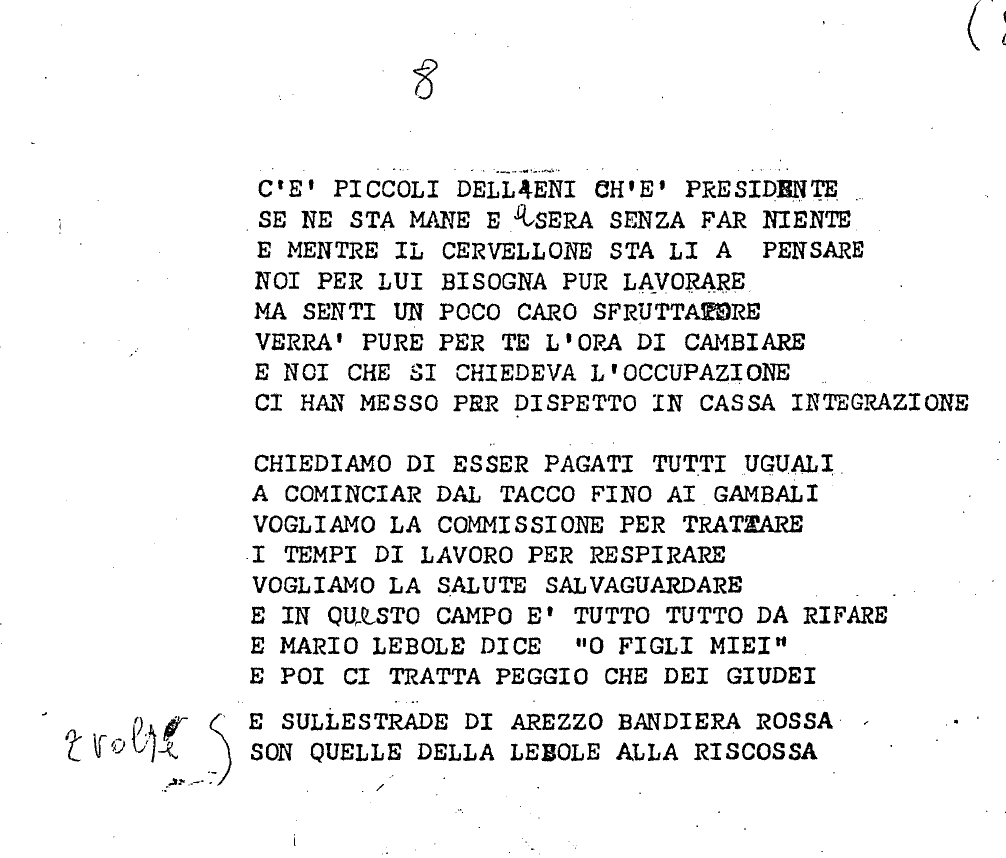

We know today that, far from diminishing or disappearing, the first three factors of hazards have been delocalized in regions of the word where laws around health, workers' safety and environmental pollution are lax, non-existent or avoidable through corruption. However, the emphasis on the mental factors impacting our lives at work intercepted precisely what the workers of Lebole experienced with the introduction of MTM methods, the process of “modernization” of the assembly line and management - soon renamed the “scientific organization of exploitation” - with the current working conditions under the algorithmic management regime.

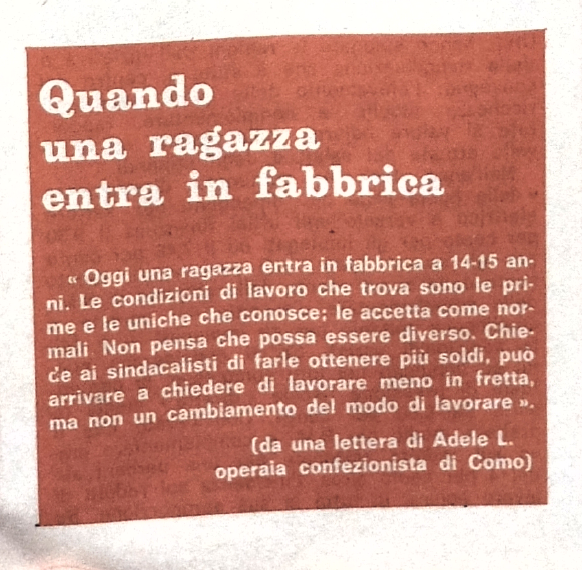

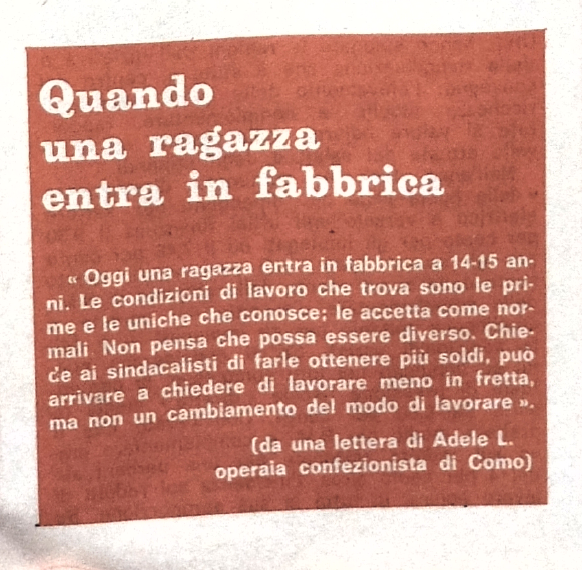

As one textile worker interviewed by Luigi Firrao put it,

Today a girl enters the factory at the age of 14-15. The working conditions she finds are the first and the only ones she knows: she accepts them as normal. She doesn’t think it can be any different. She asks the trade unionists to get her more

money, she may go so far as to ask to work less quickly, but not a change in the way of working.

from a letter of Adele L., fashion industry worker from Como

Luigi Firrao, 0101. bib⁄Battere le ciglia a comando.

As the grandaughters of that 15 year old girl, we do not know different working conditions than those we inherited as normal. Do we even know how to ask the questions that would be needed to fight off contemporary forms of technical violence, alghorhythmic expolitation and demand a change not in terms of conditions of employment, but of our way of (re)producing life?

From maddening rhythms to creepy algorithms¶

One of Amazon’s many revenue streams is a virtual labor marketplace called MTurk. It’s a platform for businesses to hire inexpensive, on-demand labor for simple ‘microtasks’ that resist automation for one reason or another. If a company needs data double-checked, images labeled, or surveys filled out, they can use the marketplace to offer per-task work to anyone willing to accept it. MTurk is short for Mechanical Turk, a reference to a famous hoax: an automaton which played chess but concealed a human making the moves.

The name is thus tongue-in-cheek, and in a telling way; MTurk is a much-celebrated innovation that relies on human work taking place out of sight and out of mind. Businesses taking advantage of its extremely low costs are perhaps encouraged to forget or ignore the fact that humans are doing these rote tasks, often for pennies.

Jeff Bezos has described the microtasks of MTurk workers as “artificial artificial intelligence;” the norm being imitated is therefore that of machinery: efficient, cheap, standing in reserve, silent and obedient. MTurk calls its job offerings “Human Intelligence Tasks” as additional indication that simple, repetitive tasks requiring human intelligence are unusual in today’s workflows.

Caging workers for their own good

A cage for workers on wheels. It sounds like the stuff of science fiction. It’s not. In 2016, Amazon filed a patent for a device described as a “system and method for transporting personnel within an active workplace”. It is actually a cage large enough to fit a worker. It’s mounted on top of an automated trolley device. A robotic arm faces outwards.

The worker cage was designed by Amazon’s robotic engineers. It was intended to protect workers in Amazon’s warehouses when they needed to venture into spaces where robot stock-pickers whizz around. Amazon’s worker cage was quietly patented and only came to global attention thanks to the diligent digging of two academics. When the workers’ cage started to appear in newspaper headlines, Amazon executives declared it a “bad idea”.

Amazon may have dropped the plans, but that should not come as a surprise. The company doesn’t need a robotic cage for workers – it already has one of the most all-pervasive control systems in history. In its huge warehouses, workers carry hand-held computers that control their movements. A wristband patented by the company (but which is not yet in use) can direct the movement of workers’ hands using “haptic feedback”. Stock pickers in Amazon warehouses are watched by cameras, and workers have reportedly been reduced to urinating in bottles in order to hit their targets, and they are constantly reminded of their productivity rates. Investigations by journalists have also exposed a worryingly high level of ambulance call-outs to Amazon warehouses in the UK.

the Amazon cage drawing that accompanies the patent

Now a days, employee health and well-being is the most important consideration in the work place. Because it will affect the productivity of an individual employee and team contribution. Eventually, the automatic facial expression analysis using machine learning has become an interesting and active research area from past few decades.In this paper, Real time Employee Emotion Detection System (RtEED) has been proposed to automatically detect employee emotions in real time using machine learning. RtEED system helps the employer can check well-being of employees and identified emotion will be intimated to respective employee through messages. Thereby employees can make better decisions, they can improve their concentration level towards work and adopt to the healthier life style and much productive work styles. CMU Multi-PIE Face Data is used to train machine learning model. Each employee will be equipped with a webcam to capture facial expression of an employee in real time. The RtEED system designed to identify six emotions such as happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, disgust and anger through the captured image. Results demonstrate that expected objectives are achieved.

How are we? On the degradation of planetary health¶

Diseases are one of the most faithful mirrors of the way man enters into a relationship with nature, of which he is a part, through work, technology and culture, i.e. through changing social relations and historically progressive scientific acquisitions.

- Berlinguer, introduction to the conference “La medicina e la società contemporanea”, Instituto Gramsci, 1967

The aftermath of WWII saw a number of struggles for health to become recognised as a common good. Many people fought for health practices to be supported via the public sector, and for care to be made available universally and for free at the point of use (that is, paid for through general taxation). Some of these struggles were more successful, other were less so, but whenever change came about it was not a top-down decision, but a result of complex mobilizations that often created transversal connections between those affected, organizers and professionals.

We focus on Italy not only because it is our context of origin, but also because during the decades 1960s and 1970s, it was an extremely lively political laboratory that became significant beyond its own context.

Italy in these decades was subjected to a fast industrialization that deeply altered the life and work patterns of many. Assembly line work, organised according to the principles of scientific management, was brutal, dangerous, poisonous and mentally alienating. It should come as no surprise therefore that the struggles for health were largely working class struggles, addressing simultaneously question related to conditions of labour at the workplace, environmental degradation, gender roles in the home and the desirability of technological innovation.

In the aftermath of the decade-long neoliberal crisis of care and the more recent pandemic, many political imaginaries related to the protection of collective health rely on mutual aid and solidarity networks. Many of the initiatives that want care to be more accessible and inclusive are set up as self-organzised practices. Many activists and organizers are loudly critical of public healthcare provisions which are perceived as negligent and over-bureaucratic at best, incompetent and punitive at worst.

Looking back at the Italian struggles for health of the 1960s and 1970s is a relevant tasks today as this history reminds us of a different possibility in orienting our political imaginaries. Rather than presenting autonomous and self-organzied practices as the opposite of languishing public infrastructures, they remind us that these very different alignment of forces is possible, as these struggles led to the creation of a public health care system in 1978.

The pressure for creating such public health care system was born from an unprecedented alliance between left political forces, advanced experiences renewing medical practice, radical health activism, struggles by trade unions, workers’ groups, student and feminist movements. The 1978 reform was a universal, public, free health service, offering a wide range of provision outside the market, largely modelled on the British NHS and reflecting the definition of health spelt out by the WHO in 1946.

Abandoning the tradition of a corporatist health system with its limited coverage of separate professional groups, Italy’s reform introduced a public and universal health service, financed through general taxation, freely available to all.

The link between the self-organized struggles and the new public system becomes apparent in the way it was designed in its original conception (albeit soon corrupted by a series of reactionary modification to the law). In several areas – mental health, occupational health, women’s health, drug treatments - new knowledge on illness prevention, new practices of service delivery and innovative institutional arrangements emerged, with a strong emphasis on territorial services addressing together health and social needs. The movements' legacy was palpable in the integrated vision of health – physical and psychic, individual and collective, linked to the community and the territory – that emerged. The struggles were clear in their proposal: a new, less hierarchical type of doctor-patient relationship was needed; healthcare should be linked to territories and, as much as possible, conducted in participatory manner; preventive approaches, rather than curing, were central in this vision. This political strategy viewed health as combining a collective dimension and an individual condition; collective struggles were therefore needed to address the economic and social roots of disease and public health problems. This approach was paralleled by the feminist movement in addressing women’s health issues, including the important experiments in self-organized health clinics. As Giulio Maccacaro had argued in 1976, the strategy was a bottom-up “politicization of medicine”, challenging the way industrial capitalism was exploiting workers and undermining health and social conditions in the country.

Politicizing Expertise, Over and Over Again

The Covid-19 pandemic brought back at the centre of attention the relationship between medical-scientific knowledge and political strategies in the field of healthcare, the very same relationship that has been the core issue in the historical struggles around healthcare that we have been encountering in the archives centred on 1960s and 1970s' experiences in Italy.

During the pandemic, the dynamics of decision-making regarding the management of the health crisis were characterised by many difficulties that brought to the surface some key aspects of the relationship between the governed and the governors, the so called ‘experts’ and those who are not; in other words, the crucial and essential nodes of democratic order.

On this terrain, all the critical signs characterising the current processes of depoliticisation that the neoliberalist governance has generated during last decades have become apparent.

Let’s be clear: the contribution of experts is relevant in order to make decisions in the most informed way possible, all the more so in situations of health emergencies; however, the massive recourse to them runs the risk of taking the place of the responsibility of politics and institutions, the risk of presenting solutions as unquestionable, just because they are ‘technically’ founded, without a common discussion on what is needed and which are priorities.

During the pandemic, this exclusion defined at least two different models of care, of taking care of the emergency. On the one side, the care proposed by governments, that has been often rhetorical and sectorial. Let’s think for instance on all dispensable bodies who were put in charge of the growing necessities of care, without receiving back any increase in wage, or at least an increase of the safety conditions in which they worked. On the other side, we have the model of care promoted by solidarity and mutual aid collectives, neighbourhoods and groups, whose aim was to redistribute the resources needed to face the emergency as much as possible, while at the same time denouncing the extremely dire conditions in which public services versed, due to decades of strategic disinvestment.

The machinic feminine, the machinic neutral¶

Terms of service

The terms of service, and the term service itself, while perfectly acceptable and of current use today in job descriptions of all kinds, shares a long history with the power asymmetry and structural violence of ‘servitude’. The epochal passage from having household servants to hiring domestic helpers did not fully dissipate the contradictions at play in this kind of work. Servile and service work share at the core of their organizational praxis a logic of concealment of their actors and operations. They share techniques of hiding the unpleasantness of work (resentment, fatigue, boredom, humiliation, and so forth) under a thick layer of expected emotional and attentive labour. This creates an social environment which is conducive to unidirectional care relations, a problem that feminist scholars still see as unresolved. We need to consider such feminist critique of the continuities between servitude, service and patriarchal expectations of comfort and convenience. These cultural assumptions have been providing the basis for developing a plethora of new digital tools and platform-mediated services: it is at this juncture that the logic of invisibilization of labour proper of servitude becomes potentiated by technology’s tendency to recede away from consciousness.

Social Reproduction and Hyperemployment

The histories of machines, femininity, and waged labour have long been understood as deeply entangled and mutually constitutive. This merging of woman, machine, and work is taken in a new direction in the twenty-first century, with the advent of the “digital assistant”. These applications are knowledge navigators, available as part of various operating systems, which recognise natural speech, and use this ability to help answer user’s queries and to aid in organizational tasks, such as scheduling meetings or setting reminders. Perhaps the most famous of these is Apple’s Siri – now widely recognised as the voice of the iPhone – but there are several others, including GoogleNow and Microsoft’s Cortana, all of which perform similar functions with varying degrees of efficiency. The connections between these digital assistants and the conventions of low-status clerical work are obvious; Microsoft even went so far as to interview human PAs whilst developing Cortana, and a reviewer from Wired magazine declared that using Siri is: ‘kind of like having the unpaid intern of my dreams at my beck and call, organizing my life for me’ (Chen, 2011: n.p.). These apps represent, in many respects, the automation of what has been traditionally deemed to be women’s labour. […] This brings us to the topic of ‘hyperemployment.’ What do we mean by this term? Hyperemployment is an idea, advanced by Ian Bogost, which links contemporary technological developments with a qualitative and quantitative change in personal workloads. His argument is that technology – far from acting in a labour-saving capacity – is in fact generative of ever more tasks and responsibilities.

from: Helen Hester, www⁄Technically Female: Women, Machines, and Hyperemployment, Salvage magazine, 2016.

Female-sounding at least

Once you start listening you can’t stop hearing it. The voice – female, or female-sounding at least, pre-recorded ‘real’ voices or mechanised tones, or, often, a weird cut-up mixture of both, dominates the sonic landscape. From the supermarket checkout machines with their chaste motherish inquiries (‘have you swiped your Nectar card?’) to repeated assertions regarding the modes of securitised paranoia (‘in these times of heightened security’), the female voice operates as a central asset in the continued securitisation and control of contemporary space, cutting across what little is left of the public realm and providing the appearance and the illusion of efficiency, calm and reassurance in commercial environments.

Make-up for the voice

Accents are a constant hurdle for millions of call center workers, especially in countries like the Philippines and India, where an entire “accent neutralization” industry tries to train workers to sound more like the western customers they’re calling – often unsuccessfully. As reported in SFGate this week, Sanas hopes its technology can provide a shortcut. Using data about the sounds of different accents and how they correspond to each other, Sanas’s AI engine can transform a speaker’s accent into what passes for another one – and right now, the focus is on making non-Americans sound like white Americans.

[…]

Narayana said he had heard the criticism, but he argued that Sanas approaches the world as it is. “Yes, this is wrong, and we should not have existed at all. But a lot of things exist in the world – like why does makeup exist? Why can’t people accept the way they are? Is it wrong, the way the world is? Absolutely. But do we then let agents suffer? I built this technology for the agents, because I don’t want him or her to go through what I went through.” The comparison to makeup is unsettling. If society – or say, an employer – pressures certain people to wear makeup, is it a real choice? And though Sanas frames its technology as opt-in, it’s not hard to envision a future in which this kind of algorithmic “makeup” becomes more widely available – and even mandatory.

In way of conclusions¶

Through the pages and the documents gathered in Maddening Rhythms we have unpacking the story of Lebole workers to disentangle some of the aspects that characterised their conditions of life, work and struggles. Our time spent in the archive we traced some of the debates , key terms and inventive organizational techniques that characterised the decades 1960s and 1970s, which as we saw marked the epochal passage to a new level of technologization of work. Our meandering through the many newspaper clips and typed manuscripts was simultaneously a quest to find tools for reading the present.

A present that we then begun to map through a number of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with fifteen workers employed in different occupational sectors, but who all share a significant relation with digital technologies as part of their job experience. We are extremely grateful to all of those who took the time to talk to us, sharing sometimes difficult stories about their work life and their relationships with co-workers, clients and (often alghoritmic) bosses. These conversations were points of entry in the simmering landscape of platform work and gig economy.

In Italy (INAP) there are over 570,000 platform workers, 1.3% of the national population. They are riders, delivery workers, AI trainers, data compilers, content creators, sex workers and many more.

50.7% of them ended up in this kind of work because they have no other alternatives. For 48% of them, platform work is their main source of income.

What emerges from the juxtaposition between past and present stories describing the work environment and its impact on health?

First of all, we found many, at times surprising, lines of continuity. Not only the obsessive rhythms of work, but also a weariness of the effects of technology on psychic and physical health; an ever increasingly “scripted” job description, where not only tasks, but behaviours and movements are meticulously monitored; the quest for ways to expand workers struggles beyond the places of work, to include demands around environmental care and reorganization of social reproduction; a call to politicize the role of experts, perceived as distant and unaware of the actual experiences of workers. But we also found some fissures, marking stark lines of discontinuity. For example, the separation between bodies at work, and its consequences that the contemporary spatial and temporal organization of labour is having on a ever-weaker social solidarity. Isolation and solitude increased a lot in contemproary accounts (as one of our interviees, Cadmioboro, put it: “we are all alone”).

Like the Leboline, the workers we interviewed are situated in a very ‘young’ technological landscape.

For instance, Angelo Junior Avelli reminded us that the introduction of food delivery platforms in Italy dates back only to 2015, and one year later we already witness the first strike action in the sector by Foodora workers, followed in 2017 by many others mobilizations, including the one at Deliveroo, which leads to the passing of the law n. 128 in 2019, a law instituting some measures of protection for riders and other platofrom workers, including compulsory insurance coverage against accidents at work and occupational diseases and the introduction of a basic salary. This resonates with the stories that Luigi Firrao heard by the Lebole worker he interviewed in 1967 and 1969, who also needed a bit of time to organize their efforts to organize and formulate demands against the new organization of their work through the MTM method.

However, a precise understanding (and, consequentially, a political awareness) of the mechanisms organizing digital work is very uneavenly spread among contemproary gig workers, who struggle to find common places (virtual or in real life) where to share their knowledges. It is not a coincidence that the most visible group, that of the rider, also shares a starker visibility in public spaces and opportunity for in-person meetings, compared to many other kinds of platform work.

Currently there are a number of fighting and resistance practices emerging within and beyond platforms, from strike actions to individual tricks adopted to slow down. Forms of self-management / ownership of the algorithm - as experimented with by the cooperative platforms movement - are also taking hold. There are those who, in continuity with the early days of industrial production, invoke forms of Luddite sabotage. Others identify in an universal unconditional basic income the only measure capable of restoring the power of the working class of rejecting working conditions that are dangerous and humiliating. Still others are engaged in new forms of unionization, such as recent attempts at Amazon, Apple and Deliveroo. Finally, there are those who see a need to deal with a more radical transformation of the digital infrastructure that regulates not only work, but ever more ubiquitously, most aspects of life. A need for a sustainable redesign of the tech sector, one that would include a consideration of its environmental impact as well as its psychological one. There all all kinds of experimentalisms agitating in the background of the platform sector, not simply reduceable to a clear antagonism, but embracing more oblique strategies of resistance and survival.

Rather than speculating on the future directions these and other protests will contribute to shape here, we wish to conclude this work in progress sharing our conviction, which grew during these months of research, around the paramount importance to conitue keeping track, in this political conjuncture, of the mutual implications and reconfigurations of welfare and technology.

Versione in ITALIANO: Eppure, non siamo robot¶

Automazione

Questa sezione finale raccoglie documenti, frammenti e approfondimenti che collegano le storie passate raccolte in queste pagine con il tempo presente. Gli ultimi due decenni sono stati segnati da un nuovo ciclo di automazione e da altri cambiamenti tecnologici che impattano i modi in cui le persone lavorano, si curano, vivono e protestano. Senza la pretesa di essere esaustive, abbiamo qui raccolto alcuni materiali che ci paiono entrare in risonanza con i quattro fils rouges introdotti nelle sezioni precedenti: tecniche di sfruttamento; condizioni sanitarie e ambientali; discriminazione di genere e forme di resistenza.

La storia da cui partiamo: Eppure, non siamo robot

Sia L’Ambiente di lavoro scritto per la prima volta sulla base dell’esperienze in FIAT che il pamphlet Contro la nocività redatto dai comitati politici di Porto Marghera concordavano nell’individuare una tendenza di medio periodo che rimane di cruciale importanza nel nostro presente: la nocività mentale.

Nel linguaggio de L’Ambiente di lavoro, si avanzava l’idea che mentre i primi tre fattori di nocività sarebbero stati mitigati dalle tendenze interne al capitalismo stesso, il quarto fattore relativo al benessere mentale sarebbe via via peggiorato:

In Contro la nocività si legge:

Nella nuova fabbrica, a fronte di una modesta riduzione delle tossicità e quindi delle malattie professionali tradizionalmente intese, si assisterà a un forte aumento dei disturbi mentali.

“Contro la nocività” (Comitato Politico, 28 febbraio 1971).

Oggi sappiamo che, lungi dal diminuire o scomparire, i primi tre fattori di rischio sono stati piuttosto delocalizzati in regioni del mondo in cui le leggi sulla salute, sulla sicurezza dei lavoratori e sull’inquinamento ambientale sono lassiste, inesistenti o evitabili grazie alla corruzione. Tuttavia, l’enfasi sui fattori mentali che impattano sulla nostra vita al lavoro ha intercettato proprio ciò che le operaie della Lebole sperimentarono tra le prime in Italia con l’introduzione dei metodi MTM. Il processo di “modernizzazione” della catena di montaggio e del management - presto ribattezzata “organizzazione scientifica dello sfruttamento” - presenta numerose continuità con le attuali condizioni di lavoro in regime di gestione algoritmica.

Come disse un’operaia tessile intervistata da Luigi Firrao,

Luigi Firrao, 0101. bib⁄Battere le ciglia a comando.

Noi ci sentiamo un po’ le nipoti di quella ragazza di 15 anni. Non conosciamo condizioni di lavoro diverse da quelle che abbiamo ereditato come normali. Ma sappiamo almeno porre le domande necessarie per contrastare le forme contemporanee di violenza tecnica, di espoliazione algoritmica per chiedere un cambiamento non solo delle condizioni di lavoro, ma del nostro intero modo di (ri)produrre la vita?

Dai ritmi forsennati agli algoritmi inquietanti

Una delle tante fonti di guadagno di Amazon è un mercato del lavoro virtuale chiamato MTurk. Si tratta di una piattaforma che consente alle aziende di assumere manodopera a basso costo e su richiesta per semplici “microcompiti” che, per un motivo o per l’altro, resistono all’automazione. Se un’azienda ha bisogno di ricontrollare dati, etichettare immagini o compilare sondaggi, può utilizzare questo marketplace per offrire lavoro a cottimo a chiunque sia disposto ad accettarlo. MTurk è l’abbreviazione di Mechanical Turk, un riferimento a una famosa bufala: un ‘automa’ che giocava a scacchi ma che in realtà nascondeva una persona che faceva le mosse.

Il nome è quindi ironico, e in modo eloquente; MTurk è un’innovazione molto apprezzata che si basa sul lavoro umano che si svolge lontano dagli occhi e dalla mente. Le aziende che approfittano dei suoi costi estremamente bassi sono forse incoraggiate a dimenticarsi o a ignorare il fatto che sono esseri umani a svolgere questi compiti routinari, spesso per pochi centesimi.

Jeff Bezos ha descritto i microcompiti dei lavoratori di MTurk come “artificiale intelligenza artificiale”; la norma che viene imitata è quindi quella delle macchine: efficienti, economiche, in attesa, silenziose e obbedienti. MTurk chiama le sue offerte di lavoro “Compiti di intelligenza umana”, come ulteriore indicazione che i compiti semplici e ripetitivi che richiedono l’intelligenza umana sono insoliti nei flussi di lavoro odierni.

Ingabbiare i lavoratori per il loro bene

Una gabbia per lavoratori su ruote. Sembra roba da fantascienza. Non lo è. Nel 2016, Amazon ha depositato un brevetto per un dispositivo descritto come “sistema e metodo per il trasporto di personale all’interno di un luogo di lavoro attivo”. Si tratta in realtà di una gabbia abbastanza grande da contenere un operaio. È montata sopra un carrello automatizzato. Un braccio robotico è rivolto verso l’esterno.

La gabbia per lavoratori è stata progettata dagli ingegneri robotici di Amazon. Era destinata a proteggere gli operai dei magazzini di Amazon quando devono avventurarsi in spazi in cui sfrecciano robot raccoglitori di scorte. La gabbia per lavoratori di Amazon è stata brevettata in sordina ed è arrivata all’attenzione mondiale solo grazie al diligente lavoro di due studiosi. Quando la gabbia per lavoratori ha iniziato a comparire nei titoli dei giornali, i dirigenti di Amazon l’hanno dichiarata una “cattiva idea”.

Amazon potrebbe aver abbandonato il progetto, ma l’iniziativa non dovrebbe sorprendere. L’azienda in realtà non ha bisogno di una gabbia robotica per i lavoratori: dispone già di uno dei sistemi di controllo più onnipervasivi della storia. Nei suoi enormi magazzini, gli operai portano con sé computer palmari che controllano i loro movimenti. Un braccialetto brevettato dall’azienda (ma non ancora in uso) è in grado di dirigere il movimento delle mani dei lavoratori utilizzando un “feedback aptico”. Gli addetti alla raccolta delle scorte nei magazzini di Amazon sono sorvegliati da telecamere e, secondo quanto riferito, sono stati costretti a urinare in delle bottiglie per poter raggiungeregli gli obiettivi richiesti, e viene loro costantemente ricordato il proprio tasso di produttività. Diverse inchieste giornalistiche hanno anche rivelato un livello preoccupante di chiamate ad ambulanze inoltrate dai magazzini Amazon nel Regno Unito.

Al giorno d’oggi, la salute e il benessere dei dipendenti sono la considerazione più importante sul posto di lavoro. Perché influiscono sulla produttività del singolo lavoratore e sul contributo del team. L’analisi automatica delle espressioni facciali tramite l’apprendimento automatico è diventata un’area di ricerca interessante e attiva negli ultimi decenni. Nel presente articolo, viene proposto un sistema di rilevamento delle emozioni dei dipendenti in tempo reale (RtEED) per rilevare automaticamente le emozioni dei dipendenti in tempo reale utilizzando l’apprendimento automatico. Il sistema RtEED aiuta il datore di lavoro a controllare il benessere dei dipendenti e le emozioni identificate saranno comunicate ai rispettivi dipendenti tramite messaggi. In questo modo i dipendenti possono prendere decisioni migliori, migliorare il loro livello di concentrazione sul lavoro e adottare uno stile di vita più sano e produttivo. Per addestrare il modello di apprendimento automatico vengono utilizzati i dati CMU Multi-PIE Face. Ogni dipendente sarà dotato di una webcam per catturare la sua espressione facciale in tempo reale. Il sistema RtEED è stato progettato per identificare sei emozioni come felicità, tristezza, sorpresa, paura, disgusto e rabbia attraverso l’immagine catturata. I risultati dimostrano che gli obiettivi ipotizzati sono stati raggiunti.

Come stiamo? Sul degrado della salute planetaria

Le malattie sono uno degli specchi più fedeli del modo in cui l’uomo entra in rapporto con la natura, di cui fa parte, attraverso il lavoro, la tecnica e la cultura, cioè attraverso il cambiamento dei rapporti sociali e le acquisizioni scientifiche storicamente progressive.

- Giovanni Berlinguer, introduzione al convegno “La medicina e la società contemporanea”, Istituto Gramsci, 1967

Il secondo dopoguerra ha visto una serie di lotte per il riconoscimento della salute come bene comune. Molte persone si sono battute affinché le pratiche sanitarie fossero sostenute dal settore pubblico e le cure fossero rese disponibili universalmente e gratuitamente al momento dell’uso (cioè sostenute economicamente attraverso la fiscalità generale). Alcune di queste lotte hanno avuto più successo, altre meno, ma ogni volta che si è verificato un cambiamento in positivo non si è trattato solamente di implementare una decisione dall’alto, ma questo è stato il risultato di mobilitazioni complesse che spesso hanno creato connessioni trasversali tra persone impattate, attivisti e tecnici.

Ci siamo qui concentrate sull’Italia non solo perché è il nostro contesto d’origine, ma anche perché nei decenni ‘60 e ‘70 il nostro paese è stato un laboratorio politico estremamente vivace e motlo significativo anche al di fuori del suo contesto specifico.

In questi decenni l’Italia fu sottoposta a una rapida industrializzazione che modificò profondamente i modelli di vita e di produzione. Il lavoro in catena di montaggio, organizzato secondo i principi del management scientifico, era brutale, pericoloso, velenoso e mentalmente alienante. Non deve sorprendere, quindi, che le lotte per la salute siano state in gran parte lotte della classe operaia, che affrontarono contemporaneamente questioni legate alle condizioni sul posto di lavoro, al degrado ambientale, ai ruoli di genere e alle opportunità aperte (o chiuse) dall’innovazione tecnologica.

All’indomani della crisi neoliberale della cura e della più recente pandemia, molti immaginari politici legati alla tutela della salute collettiva guardano all’operato delle reti di mutuo soccorso e altre iniziative di solidarietà dal basso. Difatti molte realtà che si battono per un’assistenza più accessibile e inclusiva si configurano ad oggi come pratiche auto-organizzate fuori dal contesto istituzionale. Molti attivisti e organizzatori criticano aspramente i servizi sanitari pubblici, percepiti come negligenti ed eccessivamente burocratici nel migliore dei casi, incompetenti e punitivi nel peggiore.

Guardare alle lotte italiane per la salute degli anni Sessanta e Settanta ci sembra un compito rilevante oggi, perché questa storia ci ricorda una possibilità diversa per ri-orientare i nostri immaginari politici. Piuttosto che presentare le pratiche autonome e auto-organizzate come l’opposto o il ‘fuori’ rispetto alle infrastrutture pubbliche languenti, queste lotte ci ricordano che una diversa composizione di forze è stata e forse è ancora possibile, dato che l’allineamento strategico di queste diverse lotte portò alla creazione di un sistema sanitario pubblico nel 1978.

La pressione per creare tale sistema sanitario pubblico scaturí da un’alleanza senza precedenti tra forze politiche di sinistra, esperienze avanzate di rinnovamento della pratica medica, attivismo sanitario radicale, lotte dei sindacati, gruppi di lavoratori, movimenti studenteschi e femministi.Abbandonando la tradizione di un sistema sanitario corporativo, con la sua copertura limitata a gruppi professionali separati, la riforma italiana introdusse un servizio sanitario finanziato dalla fiscalità generale e liberamente accessibile a tutti.

La riforma del 1978 instituí un servizio sanitario universale e gratuito, che offriva un’ampia gamma di prestazioni al di fuori del mercato, sul modello del NHS britannico e che rifletteva la definizione di salute formulata dall’OMS nel 1946.

Il legame tra le lotte politiche e il nuovo sistema sanitario diventa evidente esaminando il modo in cui quest’ultimo fu progettato nella sua concezione originaria (anche se molto presto questa impostazione venne corrotta da una serie di modifiche reazionarie alla legge). In diversi settori - salute mentale, salute sul lavoro, salute delle donne, trattamenti farmacologici - si generarono nuove conoscenze sulla prevenzione delle malattie, nuove pratiche di erogazione dei servizi e accordi istituzionali innovativi, con una forte enfasi sui servizi territoriali che affrontavano insieme bisogni sanitari e sociali. L’eredità dei movimenti politici era palpabile nella visione integrata della salute - fisica e psichica, individuale e collettiva, legata alla comunità e al territorio - che emergeva nel SSN. Le lotte politiche per la salute erano state chiare nella loro proposta: era necessario un nuovo tipo di rapporto medico-paziente, meno gerarchico e l’assistenza sanitaria doveva essere legata ai territori e, per quanto possibile, condotta in modo partecipativo. Gli approcci preventivi, piuttosto che curativi, erano centrali in questa visione. Tale strategia politica trattava la salute come una risultante tra condizioni comuni e esperienza individuale; erano quindi necessarie lotte collettive per affrontare le radici economiche e sociali delle malattie e dei problemi di salute pubblica. Non a caso, questo approccio emerse in parallelo al movimento femminista che metteva a tema nello stesso periodo i problemi di salute delle donne, inventando i consultori autogestiti. Come sostenuto da Giulio Maccacaro nel 1976, la strategia delle lotte italiane per la salute fu una “politicizzazione della medicina” dal basso verso l’alto, che metteva in discussione il modo in cui il capitalismo industriale sfruttava i lavoratori e minava le condizioni sanitarie e sociali del Paese.

Politicizzare gli esperti, ancora e ancora

La pandemia di Covid-19 ha riportato al centro dell’attenzione il rapporto tra sapere medico-scientifico e strategie politiche in campo sanitario, lo stesso rapporto che è stato al centro delle lotte storiche sulla sanità che abbiamo incontrato negli archivi. Durante la pandemia, le dinamiche decisionali relative alla gestione della crisi sanitaria sono state caratterizzate da molte difficoltà che hanno fatto emergere alcuni aspetti chiave del rapporto tra governati e governanti, tra i cosiddetti “esperti” e coloro che non lo sono; in altre parole, i nodi cruciali ed essenziali dell’ordine democratico. Su questo terreno sono emersi tutti i segni critici che caratterizzano gli attuali processi di spoliticizzazione che la governance neoliberista ha generato negli ultimi decenni.

Vogliamo essere chiare: il contributo degli esperti è rilevante per prendere decisioni il più possibile consapevoli, a maggior ragione in situazioni di emergenza sanitaria; tuttavia, il ricorso massiccio ai tecnici rischia di sostituirsi alla responsabilità della politica e delle istituzioni, di presentare le soluzioni come indiscutibili, solo perché “tecnicamente” fondate, senza una discussione comune su cosa serva e quali siano le priorità.

Durante la pandemia, questa esclusione ha definito almeno due diversi modelli di cura, di presa in carico dell’emergenza. Da un lato, la cura proposta dai governi, che è stata spesso retorica e settoriale. Pensiamo ad esempio a tutti i corpi che sono stati incaricati delle crescenti necessità di cura, senza ricevere in cambio alcun aumento di salario, o almeno un aumento delle condizioni di sicurezza in cui lavoravano. Dall’altro lato, abbiamo il modello di assistenza promosso dai collettivi di solidarietà e di mutuo soccorso, nei quartieri e in piccoli gruppi, il cui obiettivo è stato quello di ridistribuire il più possibile le risorse necessarie per affrontare l’emergenza, denunciando al contempo le condizioni estremamente disastrate in cui versavano i servizi pubblici, a causa di decenni di disinvestimento strategico.

Il femminile macchinico: Termini di servizio

I termini di servizio, e il termine stesso “servizio”, pur essendo perfettamente accettabili e di uso corrente oggi nelle descrizioni di mansioni di ogni tipo, condividono una lunga storia con l’asimmetria di potere e la violenza strutturale della “servitù”. Il passaggio epocale dalla servitù domestica all’assunzione di collaboratrici domestiche non ha dissipato del tutto le contraddizioni in gioco in questo tipo di impiego. Il lavoro servile e quello di servizio condividono al centro della loro prassi organizzativa una logica di occultamento degli attori e delle operazioni. Condividono le tecniche per nascondere la sgradevolezza del lavoro (risentimento, fatica, noia, umiliazione e così via) sotto uno spesso strato di lavoro emotivo e di attenzione. Questo crea un ambiente sociale favorevole alle relazioni di cura unidirezionali, un problema che le studiose femministe considerano ancora irrisolto. Pare rilevante oggi prendere spunto dalla critica femminista alla continuità tra servitù, servizio e aspettative patriarcali di comfort e comodità nella vita quotidiana. Tali presupposti culturali hanno fornito la base per lo sviluppo di una pletora di nuovi strumenti digitali e di servizi mediati da piattaforme: è in questo frangente che la logica dell’invisibilizzazione del lavoro propria della servitù viene potenziata dalla tendenza della tecnologia ad allontanarsi dalla coscienza.

Riproduzione sociale e iperlavoro

Le storie delle macchine, della femminilità e del lavoro salariato sono state a lungo intese come profondamente intrecciate e reciprocamente costitutive. Questa fusione tra donna, macchina e lavoro prende una nuova direzione nel XXI secolo, con l’avvento degli “assistenti digitali”. Queste applicazioni sono navigatori della conoscenza, disponibili all’interno di vari sistemi operativi, che riconoscono il linguaggio naturale e utilizzano questa capacità per rispondere alle domande dell’utente e per aiutarlo in compiti organizzativi, come programmare riunioni o impostare promemoria. Il più famoso di questi è Siri di Apple, ormai ampiamente riconosciuto come la voce dell’iPhone, ma ne esistono molti altri, tra cui GoogleNow e Cortana di Microsoft, che svolgono tutti funzioni simili con diversi gradi di efficienza. Le connessioni tra questi assistenti digitali e le convenzioni del lavoro impiegatizio di basso livello sono evidenti; Microsoft è arrivata persino a intervistare delle PA (personal assistants) umane durante lo sviluppo di Cortana, e un recensore della rivista Wired ha dichiarato che usare Siri è: “un po’ come avere lo stagista non pagato dei miei sogni ai miei ordini, che organizza la mia vita per me” (Chen, 2011: n.p.). Queste applicazioni rappresentano, per molti aspetti, l’automazione di quello che tradizionalmente è stato considerato lavoro da donne. […] Ciò ci porta al tema dell’“iperoccupazione”. Cosa intendiamo con questo termine? L’iperoccupazione è un’idea, avanzata da Ian Bogost, che collega gli sviluppi tecnologici contemporanei con un cambiamento qualitativo e quantitativo dei carichi di lavoro personali. La sua tesi è che la tecnologia, lungi dall’agire come un risparmio di manodopera, sia in realtà generatrice di un numero sempre maggiore di compiti e responsabilità.

Suona femmina, perlomeno

Una volta che si inizia a prestarci orecchio, non si riesce a smettere di sentirla. La voce - femminile, o almeno dal suono femminile, voci “vere” preregistrate o toni meccanizzati o, spesso, uno strano miscuglio di entrambi - domina il paesaggio sonoro. Dalle casse del supermercato con le loro caste domande materne (“ha strisciato la sua carta Nectar?") alle ripetute affermazioni sulle modalità della paranoia securitaria (“in questi tempi di maggiore sicurezza”), la voce femminile opera come risorsa centrale nella continua securizzazione e nel controllo dello spazio contemporaneo, attraversando quel poco che resta della sfera pubblica e fornendo l’apparenza e l’illusione di efficienza, calma e rassicurazione negli ambienti commerciali.

Trucco per la voce

L’accento è un ostacolo costante per milioni di operatori dei call center, soprattutto in paesi come le Filippine e l’India, dove un’intera industria di “neutralizzazione dell’accento” cerca di addestrare i lavoratori a parlare in modo più simile ai clienti occidentali che chiamano, spesso senza successo. Come riporta SFGate questa settimana, Sanas spera che la sua tecnologia possa fornire una scorciatoia. Utilizzando i dati relativi ai suoni dei diversi accenti e alla loro corrispondenza, il motore AI di Sanas è in grado di trasformare l’accento di un parlante in un altro - e al momento l’obiettivo è far suonare i non americani come gli americani bianchi. […] Narayana ha detto di aver accolto le critiche, ma ha sostenuto che Sanas si avvicina al mondo così com’è. “Sì, è sbagliato, e noi non dovremmo esistere affatto. Ma nel mondo esistono molte cose: perché esiste il trucco? Perché le persone non riescono ad accettare il loro modo di apparire? È sbagliato il modo in cui va il mondo? Assolutamente sì. Ma allora lasciamo che gli operatori [di call centre] soffrano? Ho costruito questa tecnologia per loro, perché non voglio che passino quello che ho passato io”. Il paragone con il trucco è inquietante. Se la società - o, per esempio, un datore di lavoro - obbliga alcune persone a truccarsi, si tratta di una vera scelta? Anche se Sanas inquadra la sua tecnologia come opt-in, non è difficile immaginare un futuro in cui questo tipo di “trucco” algoritmico diventerà sempre più disponibile, e persino obbligatorio.

Conclusioni temporanee

Attraverso le pagine e i documenti raccolti in Ritmi da pazzia abbiamo spacchettato la storia delle operaie della Lebole per districare alcuni degli aspetti che hanno caratterizzato le loro condizioni di vita, di lavoro e di lotta. Nel tempo trascorso in archivio abbiamo ripercorso alcuni dei dibattiti, dei termini chiave e delle originali tecniche organizzative che hanno caratterizzato i decenni ‘60 e ‘70, anni che come abbiamo visto hanno segnato il passaggio epocale a un nuovo livello di tecnologizzazione del lavoro. Il nostro girovagare tra i numerosi ritagli di giornale e i dattiloscritti è stato contemporaneamente una ricerca di strumenti di lettura del presente.

Un presente che abbiamo poi iniziato a mappare attraverso una serie di interviste approfondite e semi-strutturate con quindici lavoratori impiegati in settori professionali diversi, ma tutti accomunati da uno stretto rapportarsi con le tecnologie digitali come parte della loro esperienza lavorativa. Siamo estremamente grate a tutt* coloro che hanno dedicato del tempo a parlare con noi, condividendo storie a volte difficili sulla propria vita lavorativa e sui rapporti con colleghi, clienti e capi (spesso algoritmici). Queste conversazioni sono state ulteriori punti di ingresso nel panorama in ebollizione del lavoro su piattaforma e della gig economy.

In Italia (INAP) ci sono oltre 570.000 lavoratori su piattaforme digitali, l'1,3% della popolazione nazionale. Si tratta di rider, fattorini, formatori di AI, compilatrici di dati, creatrici di contenuti, lavoratori del sesso e molti altr*. Il 50,7% di loro è finito in questo tipo di lavoro perché non aveva altre alternative. Per il 48% di loro, il lavoro su piattaforma è la principale fonte di reddito.

Cosa emerge dalla giustapposizione tra storie passate e presenti che descrivono l’ambiente di lavoro e il suo impatto sulla salute?

Innanzitutto, abbiamo trovato molte linee di continuità, a volte sorprendenti. Non solo i ritmi ossessivi del lavoro, ma anche la stanchezza per gli effetti della tecnologia sulla salute psichica e fisica; una descrizione del lavoro sempre più “scriptata” o coreografata, in cui non solo i compiti, ma anche i comportamenti e i movimenti sono meticolosamente monitorati; la ricerca di modi per espandere le lotte al di là dei luoghi di lavoro, per includere richieste relative alla cura dell’ambiente e alla riorganizzazione della riproduzione sociale; la volontà di politicizzare il ruolo degli esperti, percepiti come distanti e inconsapevoli delle esperienze reali dei lavoratori. Ma abbiamo anche trovato alcune spaccature, che segnano linee di discontinuità. Ad esempio, la separazione tra i corpi al lavoro e le conseguenze che l’organizzazione spaziale e temporale contemporanea del lavoro sta avendo su una solidarietà sociale sempre più debole. L’isolamento e la solitudine sono aumentati molto nei racconti contemporanei (come ha detto uno dei nostri intervistati, Cadmioboro: “siamo tutti soli”).

Come le Leboline, le lavoratrici e i lavoratori che abbiamo intervistato si trovano in un panorama tecnologico molto “giovane”. Ad esempio, Angelo Junior Avelli ci ha ricordato che l’introduzione delle piattaforme di food delivery in Italia risale solo al 2015, e un solo anno di distanza assistiamo già alla prima azione di sciopero nel settore da parte dei lavoratori di Foodora, seguita nel 2017 da molte altre mobilitazioni, tra cui quella di Deliveroo, che ha portato all’approvazione della legge n. 128 nel 2019, una legge che istituisce alcune misure di tutela per i rider e altri lavoratori delle piattaforme, tra cui una copertura assicurativa obbligatoria contro gli infortuni sul lavoro e le malattie professionali e l’introduzione di un salario di base. Questo fa il paio con le storie che Luigi Firrao ha ascoltato dalle operaie della Lebole intervistate nel 1967 e nel 1969, le quali ebbero bisogno di un po’ di tempo per organizzare i loro sforzi e formulare richieste controi nuovi ritmi di sfruttamento dettati dal metodo MTM.

Tuttavia, la diffusione di una precisa comprensione dei meccanismi che organizzano il lavoro digitale (e, di conseguenza, una consapevolezza politica) è molto disomogenea tra chi vi lavora oggi. Emerge una fatica a trovare luoghi comuni (virtuali o nella vita reale) dove condividere le proprie conoscenze. Non è un caso che il gruppo più visibile, quello dei rider, condivida anche una maggiore visibilità negli spazi pubblici e possibilità di incontri personali, rispetto a molti altri tipi di lavoro su piattaforma.

Attualmente stanno emergendo una serie di pratiche di lotta e resistenza all’interno e al di fuori delle piattaforme, dalle azioni di sciopero a strategie individuali adottate per rallentare i ritmi e aggirare i controlli. Stanno prendendo piede anche forme di autogestione e co-proprietà all’algoritmo, come nelle sperimentazioni portate avanti dal movimento delle piattaforme cooperative (platform cooperativism). Inoltre c’è chi, i sta invocando nuove forme di sabotaggio luddista, in continuità con quanto accadde durante i primi tempi della rivoluzione industriale. Altri ancora individuano nel reddito di base universale e incondizionato l’unica misura in grado di restituire alla classi subalterne il potere di rifiutare condizioni di lavoro pericolose e umilianti. Altri ancora si stanno impegnandoi in nuove forme di sindacalizzazione, come in recenti tentativi presso Amazon, Apple e Deliveroo. Infine, c’è chi vede la necessità di affrontare una trasformazione più radicale dell’infrastruttura digitale che regola non solo il lavoro, ma, in modo sempre più ubiquo, la maggior parte degli aspetti della vita. È necessaria una riprogettazione sostenibile del settore tecnologico, che tenga conto sia del suo impatto ambientale che psicologico. Sullo sfondo dell’economia di piattaforme si agitano sperimentalismi di ogni tipo, non semplicemente riducibili a un chiaro antagonismo, ma che abbracciano strategie più oblique di resistenza e sopravvivenza. Piuttosto che speculare sulle direzioni future che queste e altre proteste contribuiranno a delineare, desideriamo concludere questo zine e riflessione ancora aperta condividendo la nostra convinzione, maturata in questi mesi di ricerca, sull’importanza fondamentale di continuare a tenere traccia, in questa congiuntura politica, delle reciproche implicazioni e riconfigurazioni di infrastrutture del welfare e tecnologia.

doc⁄Quando un cervello elettronico è 'assunto' al posto degli operai

Quando un cervello elettronico è “assunto” al posto degli operai¶

by Diamante Limiti

Lanerossi Schio: An article describing what happens in a large textile industry when IBM reorganizes the entire production cycle: increases production is accompanied by decreases employment and falling family wages - How do workers react?

Article from Fondo Luigi Firrao:

Diamante Limiti, 0101. bib⁄Quando un cervello elettronico è "assunto" al posto degli operai.

doc⁄Più posto per le macchine e sempre meno per gli operai

Più posto per le macchine e sempre meno per gli operai¶

by Piero Campisi

An article addressing the rising unemployment resulting from the reorganization of work and “technological investment”. Examples from the RIV and FIAT in Turin, who are hiring but to such an extent that they would not even cover the renovations of the last two years. The realization is that there is no entrepreneurial drive capable of absorbing manpower.

Article from Fondo Luigi Firrao:

Piero Campisi, 0101. bib⁄Più posto per le macchine e sempre meno per gli operai.

doc⁄La maggioranza deviante. L'ideologia del controllo sociale totale

La maggioranza deviante. L’ideologia del controllo sociale totale¶

by Franco Basaglia and Franca Basaglia Ongaro

«Modern population - writes the American psychiatrist Jurgen Ruesch quoted in this book - is made up of a central group that includes government, industry, finance, science, engineering, army and education. A circle of consumers of goods and services revolves around this nucleus. On the periphery there are also the marginalized who have no significant function in our society … " The problem of the dropout, of the deviant, of the one who does not want to belong or who cannot fit in, of the misfit for whom social constraints is too tight, therefore expands to the paradox of a sort of universal deviance. This problem and the ideology that governs it constitute the theme of this book, published for the first time in 1971.

Book:

Franco Basaglia & Franca Basaglia Ongaro, 2010. bib⁄La maggioranza deviante. L'ideologia del controllo sociale totale. Dalai Editore.

doc⁄Counterproductive. Time Management in the Knowledge Economy

Counterproductive. Time Management in the Knowledge Economy¶

by Melissa Greg

As online distractions increasingly colonize our time, why has productivity become such a vital demonstration of personal and professional competence? When corporate profits are soaring but worker salaries remain stagnant, how does technology exacerbate the demand for ever greater productivity? In Counterproductive Melissa Gregg explores how productivity emerged as a way of thinking about job performance at the turn of the last century and why it remains prominent in the different work worlds of today. Examining historical and archival material alongside popular self-help genres—from housekeeping manuals to bootstrapping business gurus, and the growing interest in productivity and mindfulness software—Gregg shows how a focus on productivity isolates workers from one another and erases their collective efforts to define work limits. Questioning our faith in productivity as the ultimate measure of success, Gregg’s novel analysis conveys the futility, pointlessness, and danger of seeking time management as a salve for the always-on workplace.

Book:

Melissa Gregg, 2018. bib⁄Counterproductive.

…

… …

…

…

…

…

… …

… …

… …

… …

… …

…

…

…

….

…. ….

…. ….

…. …

…

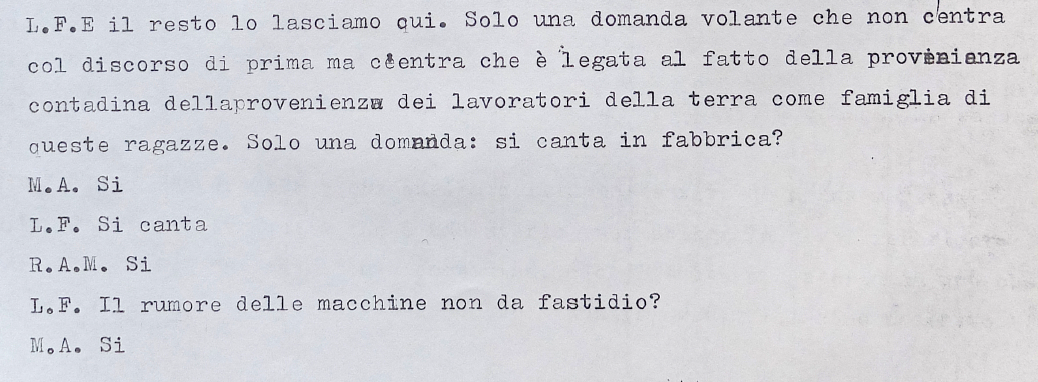

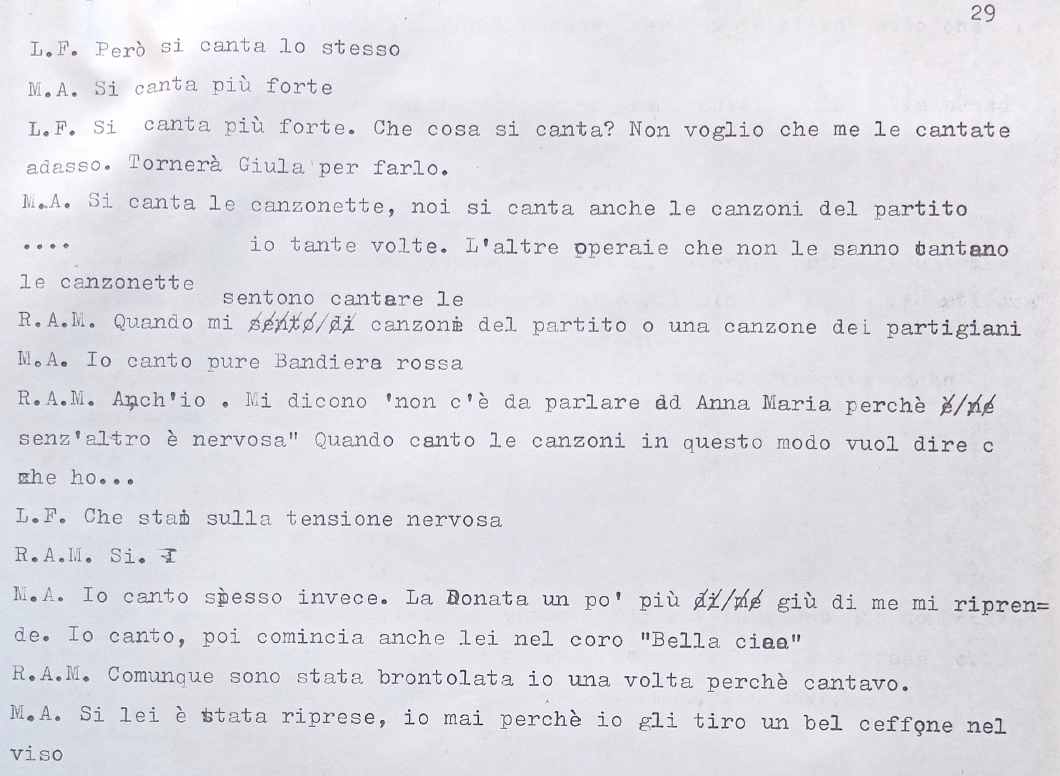

Women University 150 hourse course in Milan

Women University 150 hourse course in Milan …

… …

… …

… …

… …

… …

… …

… …

… …

…